Interview with Dr Joyce Jackson

LD has a wide ranging discussion with Dr. Joyce Jackson the newly elected Chair of the LSU Department of Geography and Anthropology. Dr. Jackson describes what it was like in undergraduate and graduate school at LSU during the early seventies, the problems she faces as the first female Chair and person of color and her vision for the future. Great history lesson on growing up in the south, studying African cultures as well as history of New Orleans, Creoles, Indians and Mardi Gras (Carnival) Indians along with LD’s unique take on everything. LD Azobra formerly known as Lyman White gives his thoughts on current events and asks questions like who should apologize. Dr. Jackson also appears on Episode 32 Dr. Seck Pt2.

Dr Joyce Jackson and LD Azobra

Transcript for Interview with LSU Chair, Department of Geography and Anthropology Dr. Joyce Jackson

Good evening. Good evening. Good evening it’s 4 PM. Stand up It’s Count Time, time for every man and woman to stand up and be counted. Welcome to another edition of Count Time podcast. I am brother LD Azobra formerly named Lyman White. Thank you for joining us today.

Today we got a very special guest. A Beautiful. Awesome. Young lady who will bring a lot of knowledge, history and great information to you. I’ve been knowing her for quite some time. She’s a friend that I knew her wonderful husband Nash we got here on out is going to be one of our legendary segments called the living Legend’s she’s a legend amongst many of us here. We got here, Dr. Joyce Marie Jackson. Welcome.

Thank you. Thanks for having me on the program.

We, we excited about you about your history, uh, all the knowledge that you can bring forward. And I don’t even know where to get started at, but I know you, your history starts back at this big school and university. They call Southern Lab connected to Southern University. In the last couple of months. And that was a great honor that came to you. You was selected, elected not for no political office right? Probably requires being a little political. So she is the first of her gender to be the first female chair of our department at LSU. What is it?

Department of Geography and Anthropology?

What is that department? You know, we don’t, most people don’t know what y’all do over there.

Well, it’s in the complex, the geoscience complex in Russell and we’re a joint department of geography and anthropology. And of course geography is the study of so many aspects of land and anthropology So many aspects of humans. And there are certain sub-disciplines to each one. And in our department we have like I said, various sub-disciplines. And so it’s sort of a complex department because of that. And it’s because of the combination of the two disciplines, but it works well. This is a good marriage. So we have separate PhD programs and, you know, separate bachelor’s and master’s programs. So, we are separate in a way, but in another way, we are certainly close together. That’s the part about geography. We have a climate center, we have a regional climate center and the rec the climate center, and we have the state climatologists.

So that’s a big part of the department. Oh yes.

And, um, they get large grants. And so they, they are big in big impact, not only for our department, but for the college college, we’re in college of humanities and social sciences. So it’s, it’s a huge impact. And

It also studied hurricanes and those types of things too. Right.

Disaster science. Is under there? A sub-discipline

I know that’s not your department, but it’s interesting that most hurricanes come off the coast of Africa and you never hear a hurricane with African name.

because they name the hurricanes from here.

But they come off the coast of Africa. That’s interesting. [inaudible] give them hispanic names, german names that has kind of interested. How long has the department been on LSU campus? 93 years. 93 years. You are the first female. And I don’t like saying it, but they say women of color to be the chair of that department. That’s correct. And 93 years. So you saying that field was dominated by men for many years? Yes.

For many, many years. All of those years,

What is your, you also told me you was, how long have you been at LSU?

Well, it depends. You weren’t taking my years. Oh yeah. That’s interesting. Yeah. Um, yeah, I have two degrees from LSU. I’m a dual, uh, alumni. You might say I have a bachelor’s and a master’s from Elisha. And, um, so I took me six years. I had, uh, four years to get my bachelor’s two years for the master’s program and I was in music school. So yeah, I did I get from music, you, most people ask that question. How did you get from music to anthropology? Well, actually I went on Indiana university for my PhD and, um, I was able to, or an, a degree in folklore and EFL musicology. And of course, you know, we had an anthropology courses too. So a folklorist ethnomusicologist can also work in an anthropology department or music or English, you know, but I chose the cultural side and I do, um, you know, folklore and ethnomusicology. And I basically look at myself as a cultural ethnographer because we all have to do field work. It’s, that’s a major part of the discipline and anthropology. Um, geography, folklore, there’s some musicology, that’s a major part of what we do is feel

Work well, none of that is let’s talk about stuff we all connect together with. So you also, when you attended LSU, what year was that?

I started at LSU in 1968 as a freshmen, 64 Years after integration. And you grew up where’d you grow up? I grew up at the foot of Southern. You might as well say at the fiddle Southern university. I went to Southern university laboratory school and we lived right off the campus of probably a mile from the campus. So I, and my mother was an administrator professor and administrative of the university. So I grew up, I might say, on the campus of Southern university.

And so you went to Southern layout right there at Southern universities. You did not attend these Southern university? No, not the university there then,

Um, uh, lived on the campus because my mother was working there and I was interested in music and I was attending everything just about the music school had as far as performances, recitals, all sorts of concerts and everything. I knew a number of the professors. Um, I didn’t take, uh, I took piano with, uh, Mr. Davos, which was one of the major PN pianists, uh, at the university. And my sister studied with another professor there at the university. So, uh, Myrtle David. So we were just, you were there all the time. And I knew that music school side, I think I wanted just more of a challenge. And I certainly got, when I went down the street to Ellis, what

Do you mean you have more of a challenge? Well,

I mean, as far as the music school was concerned, there was more, they had more practice rooms, um, more band equipment, um, more technology. I mean, just everything that was more of at LSU than was at Southern. I didn’t know those professors of course, but, um, so I just wanted, that’s what kind of challenged, I just wanted more

Was part of the challenge.

Part of the challenge that I didn’t really think about a whole lot was going into a predominantly white situation where I just left the predominantly black situation. I mean, you know, it was there, but, you know, I didn’t really, um, I, you know, it, it wasn’t a barrier. I just decided to go for it. And that’s what I did. And, uh, it was rough. I’m not gonna say it was not an easy, I mean, you talking about the chilly climate, it wasn’t chilly. It was cold

All the time in the middle of stuff.

Yes, it was. But you know, you, you go through situations like that and you have things and, you know, we discuss it amongst ourselves. You, the, other of the, of the students of color that were at LSU, we lived on and on campus for all four years. And when I was, um, you know, working on my bachelor’s degree and there were incidents and we talked about them, you know, what each other, but, and maybe, maybe when our parents, but I even stopped talking about them to my parents, because they would think about taking me out and, you know, things like, you know, you walk into class and, you know, there’s a lot of students on the sidewalk and somebody just knock you off the sidewalk, you know, and you don’t know who it is because it’s, you know, it’s a group of people walk and you go through, even in the hallways, I remember an Allen hall, you know, the, the, the halls would be full when you’re changing classes and people would just hit you just do something and keep on walking. I mean, I had people I was spat on. Um, yeah. Okay. Well, yeah, so that happened. And I remember one day I was shot with a pistol water pistol. Uh, as I was walking along Highland road, uh, on the sidewalk, I’ll never forget. I was almost in front of the law school and, uh, they just drove back in the car and shot me with water, drove down, turned around, came back and did it again. So, you know, you go through things like that and, you know, it’s, there are small incidents to some people, but they tend to Mount up after a while

Said, well, you should have known that when you win the game, this is

Ridiculous. Yeah. Well, you know, I saw some of my classmates in high school actually go to some of the, uh, predominantly white high schools. Some came back because of the situation in some state, but, um, several of them came back to the lab school and they did it in high school. So I figured, well, you know, I’m in college now, you know, I have to kinda make it on my own, figure it out and go for

It. Yeah. Also you join LSU drill team.

Yes. Um, I had, uh, been very active at the lab school and in the different extracurricular activities, you know, I was in the choir, you know, that’s, L’s a thespian in the drama society and, you know, the various organizations. So when I went to LSU, I didn’t want to just go to class. I wanted to be involved in some type of extracurricular, you know, activity in an organization. So three, three of us decided we weren’t going along. We’ve had two of my buddies, you know? So it was three of us decided that yes, um, Loretta Verdo and rose Rochet, and we were pulled out yes. And rose. Um, Loretta Verdo was, uh, a classmate of mine at the lab school. And then we met rose when we got to LSU and we were all in the same dormitory and freshmen dorm. And so we all did, we were all very active, you know?

And so we don’t figure out something for us to do this outside of our classroom. I have no idea how we came up with the coed affiliate, Persian rifles, co-ed affiliate Persian rifles. We were the affiliate to the, we actually had real rifles. Then they did, you know, fancy drill with rifles where there was a girl team that did fancy drill too, would play rifles. Okay. Well, we had to dress out at all the home games in, you know, dressing up blue and white goods. That was, was military school. And so we, you know, learned all the aspects of being in the military, had to dress out for every game. And we decided, and that’s what we did. Don’t ask me why to call it a Philly person. Right. None of us can figure out, figure it

Out. We

Did it, we did it for a year going into the second year, but, uh, rose and Loretta left and went to sup well, yeah, because yeah, because of the environment, you know, it was, it was [inaudible] and yeah, it was in some of the classrooms, you know, we felt good and dorms and we could, you know, kind of lean on each other, but we all had this different disciplines. So we were all in classes by ourselves. And you know, some of the teachers were not fair, you know, different things happen. Like some of the things I just shared with you and they were happening with us as we were by ourselves, not ne not usually in a group. Cause when you’re by yourself, somebody could do something and just keep on going. And you don’t know who it is. You don’t even know who to report.

Well also when, uh, when you were with the Persia for rifle rifle, yeah.

Co-ed affiliate perimeters rivals. Yes. We traveled. I remember once we went to Alabama, you know, going with the guys, they did comp competitive drill and we’re just, you know, dude, I love fancy drill. We were in a really nodding com competition within and the other, uh, girl, real teams. But we would go with the guys and uh, you know, do our little drill. And I remember this, this, this one time we were going to through Alabama and they would stop. We went to the university station wagons

And they would stop. So everybody wrote in the station where he was, but he didn’t know bus.

Yeah. We, we were, we wrote in the station where I think they had the guys in the vans, but we wrote in the station waives the girl teams. So they were, uh, stopping at different points at different restaurants. And they said, oh, we go in there and to see how to menu is. And so we kind of looked at each other, see how the menu is, you know, maybe all those should go and look at the menu. So after the third time we figured out that they were stopping to see if they would serve blacks in the restaurants and particularly blacks with whites in the restaurant together. So

That’s, that was like the green book in another way. Yeah, yeah.

Yeah. Who did stay down a little while longer, but when, when Miranda, when Loretta Aaron Rose left, I left too. I just didn’t go back. But they left and went to Southern university, but you didn’t leave. I stayed.

You stayed in persevere persevere. And you graduated from such familiar as you.

And what happened at the graduation? Well, I had a bachelor’s in, uh, uh, musical performance, both a performance. And I decided to stay for the masters only because of Dr. Quarterly to Astra Cuneo. And she was my applied vocal music teacher. And she, you know, she was a minority too. She was from the Philippines. She used to push me. She was my driving horse. She was my mentor in the music school. And she pushed me hard. And you know, she would, she would, she would force me to, um, to, to, to audition for different things. And most of the time I wouldn’t get them, but you know, sometimes I did, when I got to the master’s level, I did get a couple of performance, you know, solo performances and some of the things. But, um, she was the one that pushed me and pushed me and she would even talk to my parents, you know, she would call my parents. She says, she’s done. No, don’t, don’t, don’t encourage her to leave. We want to hear, you know, she, she kept me there. That was the only because of her that I stayed for my master’s degree.

[inaudible]

Yeah, they were long gone. They left, went to Southern. Did quite well at Southern university.

No, I haven’t been rules was a desk and all this other opportunity would have never happened. Not at that particular time have charter sorority. Which one is that?

Oh yeah. Um, I’m a charter member of Delta Sigma theta at LSU. We were the first, uh, black sorority on the campus. We chartered it in 1972 out of data

[inaudible]

You had to have nine to charter. And I asked me all the names we had nine y’all have y’all started, uh, is iota data, chapter Delta Sigma data incorporated. And it was a two alumni chapters that charter the chapter at LSU. So you have the bandwidth deltas and the bandwidth sigmas charter the chapter at LSU.

And you also are the link. Yes. Lynx incorporated. Well,

The lease is another organization service organization of a women of African descent. And we have 16,000 members. It’s an international organization because there are chapters in Jamaica, uh, Liberia and London. So it’s an international organization to

Work directly with them.

Yeah. We have a chapter. We have two chapters here. Uh, my chapter is bandwidth chapter and Baton Rouge chapter, the links incorporated. And then we have the black cap, a towel chapter of the links incorporated. They are the youngest chapter. We were the oldest and we have a, yeah. So it was about 16,000 women. Yeah, I am Rotarian. No, no. I’m secretary of the, uh, uh, the capital city rotary club. Well, you know, I always wanted to do service to my community and I figured the best way to do it is to be launched the organizations that you can get more, it’s more impactful if you do it that way. You know? And so I, I knew about the deltas in high school. I was a Dale Sprite and, um, I would go on the campus again. So on university campus, and these are the sororities and fraternities I would see. And I had deltas that I knew personally. So of course they would always talk to me about the Delta, but I, when I went to LSU, I, we didn’t have any, so what’d you do, if you don’t have it, you try to start it. Right. So a group of us got together and we decided that we wanted to be deltas. And so we started talking to the alumni chapters and to see what to do

In 1970, in 1972,

We charted out a data chapter,

But do you end up renting it from LSU? What was your next adventure?

Uh, I, you know, I did the masters there too in vocal performance and vocal.

Oh, you did the masters right behind it. Yes.

I just started to stayed on because that, you know, I had that professor that was pushing me, that’s the core belief to Esther KVO. She was still there. And, uh, she, uh, encouraged me to stay on for the master’s degree and, and, you know, continue to work with her in vocal performance.

And so she was in your car. So you ended up getting in a bachelor and masters back to back at LSU. That was a major accomplishment, particularly there, hang in there that long I was

Hanging in there. Well, you know, it, I think along with her, which was, she’s a very, you know, just an extraordinary woman, but it was my family, too. My parents, they were, I used to call them my bookends, you know, because, you know, they supported me. They really supported me in everything with the all app performances, whether add a solo part of that, they were, they, you know, they were there because my, my, uh, dad, uh, you know, my mother, you know, my mother has three degrees from Southern and my, my dad was a laborer at Exxon. And was it so standard art when he started. And of course now is Exxon standard all company. And he was a laborer. He only made it to the 10th grade in high school. And he, um, you know, attain of your high school in Zachary. But he, he was so determined to get his high school diploma that even after working at the plant, he went to night school. So he would finish, um, his, you know, so you get his high school diploma. He went to night school. I remember that. Uh, and, uh, and he always told me, he said, baby, you say, you go go. As far as you can go. And dad is going to help you. He said, I want you to go much more than an idea. And so that’s what he did.

And you name, it was also Mason. Yes.

He was in the Masonic order. Yeah. So several oh, he was in Schreiner is in the consistory. He was a 33rd degree, Mason.

Yeah.

Very important in our family masons and Eastern star,

But you didn’t follow the dose. No,

I, I was in the youth fraternity, but I didn’t go any further than that. I mean, it was just, you know, I was, I had to go to everything with it, everything that your children could go to.

Now, you ended up after your master’s degree, what was your head where you end up in your doctorate,

Indiana university in Bloomington, Indiana.

[inaudible] well,

Um, Dr. Raff Appleman who’s over the vocal music research department at Bloomington came to LSU to do a sort of like, uh, artists and resident for a little, for a little while at LSU. And so he did a workshop and he wanted to use [inaudible] students. And so he wanted to use me for one of his demonstrators. And so after he used me for a demonstrator, he say, when you finish here, you need to come then. Yeah. What I’m thinking and yeah, I’ll go to India. And of course, Dr. Helio, um, encouraged me to go to, she sees continuing voice. That’s the best place you can go to. And it really was. And Deanna has a school. The music school consisted of about 3000 students in the music school, alone, all bags. So, you know, some HBCU don’t have 3000 students in it, but, uh, it was, uh, it was, uh, it was a great experience is one of the best music schools in the country.

You know, when a lot of the, the performance at the met finish say, go to Indiana to teach. And after they retire from the stage, they go to Indiana university to, I was really honored, you know, for him to, to, uh, invite me. I didn’t want another, I didn’t want a PhD. I didn’t want another degree. I just wanted to go for further study. No, I wasn’t looking to get another degree in music, another PhD at, oh, I just wanted to sing the same saying it. No problem. So I went to, um, work with him and, uh, yeah. You know, he was, I mean, an excellent vocal pedagogy in vocal pedagogy, in vocal music. And, uh, he was still singing an opera himself and, and doctor that the apple one was probably in his seventies at that time, but he performed until he was wearing his eighties.

So what, what are, what are some new, what was the exciting part about going to Bloomington Indiana? What did you like about the university? What groups mixed up?

You know, when I was thinking about going, cause they had invited me, but you know, I was thinking about, and so of course I looked it up to see what else they had to offer. And I go down, you know, take a few classes, apply vocal music and you know, this is whatever else I wanted to take, you know, checked out to see what else do they have. And I saw they have a black music center music, a black had a black music research center. And, um, so that definitely piqued my interest because at LSU I didn’t do probably in the black music. I, I asked my professor if I could do something on my recitals, you know, I had a bachelor’s recital and I had a master’s recital. So I w you know, mom, you made me do a spiritual or two, but I really started looking at black composers and I wanted to perform some of their works. So I thought, wow, black music center that really intrigued me. So I started checking into that and to see whatever, what else they offer, you know, as far as black music was concerned. Well, so not only that, but they had a black studies program and they had an African studies program. The black music sends in a black art Institute. All of this was at Indiana university.

Yeah. Well, late seventies, early eighties. Yeah. In 94, we have a, um, you know, we got the black, but the

Actual department, they just got that last year. LSU.

Yes. We had a program. We had a, uh, program and the other head of department of African-American studies. They had a full department of African studies and African American arts Institute and a black cultural center. All of that was in Indiana when I got there. And that was late seventies

And it was full

Palace, like seven habit. [inaudible] very excited because I’ve

Seen people like you that’s made it more exciting, or just because you can learn more about your culture. I had

Never had a black professor, never in a university system. So I had a couple of black professors. Most of them were black as a matter of fact, when I, cause I did a ma I did well later on when I decided to go for a PhD, I did the African-American studies minor. And, uh, I did, you know, instructional systems technology. And then I did an African mine. I didn’t actually officially do that. I did the coursework, but I don’t know, officially apply for the African studies minor, but it was just so, I mean, I had three minors.

You got that excited. I guess you feel deprived at LSU.

I felt depressed because I didn’t have anything. Um, you know, anything along in terms of black studies. And it was few when I was there. No black studies, no black professors, none of that, the geography and anthropology department. How many of y’all, how many,

I’m the only black professor? How many of us even entertain getting to get going into, into that politics?

Well, that, um, that’s another situation because, um, a lot of students, you certainly don’t hear about this in high school. Now I have this taken on my own to go into some of the schools that have predominantly black students, uh, to introduce them to anthropology, folklore ethnomusicology deals, where we can study ourselves. And, you know, because at one time, even these fields, you didn’t study yourself, you studied the other comparative studies, you compare it basically compared it with European culture and say, and or whatever you don’t, you don’t do your own. You don’t study your own self that you can’t be objective enough. So you have to study the other. And that’s the only anthropology was for a long time. We just, you know, um, folklore to, you know, at least disciplines, they were comparative. We had comparative musicology where you compare again, European music with indigenous music or whatever else. The F you know, the folk music is of that country. Now you can study European music in ethnomusicology. Now you can study any music of the world that you want to study in as in the field of ethnomusicology, but you couldn’t do that 60, 70 years ago,

Tight, tight hair, what you can do and how

You can do. And so here I am an Indiana university. You mean, I can start my whole mouth. I was elated, and I know you can do that, but here’s, I’m at this place now that I can actually do this

Loud to really drive

And in my own working with my own culture, music, folklore. Oh. And I, you know, things come up in the folklore class, I say, slander dozens, dueling, verbal duel, laying on the streets and toasting the toast tradition. [inaudible], it’s like learning something new,

Wonderful, awesome experience at the university of Indiana, Indiana university, university in Bloomington, Indiana, south at LSU. So you had that great of a time. What brought you back here?

Well, I have the wildlife, you know, my professors, my professors file it, you know, was telling me why don’t you just go on and apply for the degree? Cause I was just taking courses. So I went on and applied for the PhD in, uh, and I decided to go the folklore and ethnomusicology route instead of, you know, like anthropology or music. I didn’t want another degree in music. And, uh, I felt more at home in folklore and ethnomusicology and so joint degree again in folklore and ethnomusicology and um, so I finished the PhD there. Um, but before I finished, I was working on my dissertation and trying to work, finish up a dissertation, working two or three little jobs, you know? Well, I, I came back home to new Orleans to work, do my field work for the dissertation, which is a major thing we have to do as a field work.

And I was, I decided to do mine in gospel music. Well, initially I wanted to go to Africa and study the Sujata epic in Mali. So I took two years of bombard preparing to go to Mali, but I never did get the money. I never did get the fellowship to go. So I said, at what else can I do that really interests me and study of gospel music. Um, my parents, my father had a singing group in his family, the Jacksons and they, you know, perform gospel music. And then I used to hear quartets and all that. And I said, well, I think I’ll do something where we have a void. And there was a void in quartets, you know, in the study of quartets. So that’s what I chose to do. So I moved back to new Orleans to do the field work for my dissertation.

And after I did a lot of field work there, I stayed there for a year. It was kind of like a little group here. I follow quartets around gospel quartets and interview them, you know, and observe them in the context of, um, you know, in the contextual setting of the churches of whatever community centers it was singing in. So I studied that for a year, just going around new Orleans and doing that. I did once move in Baton Rouge that I grew up hearing. And so I included them, um, you know, talk to some of my travelers, Zion travel, spiritual singers, uh, work with them. And Ben ruins, Zion harmonizes in new Orleans.

Now you told me that when you attended LSU, they told you to get to that the same.

Yeah. Uh, it’s not the same gospel music. They thought that gospel music would destroy my voice.

That’s where your boys come from. They literally told you that the same. So you couldn’t say in gospel music, why use it attended LSU?

I, I was in my church choir. I got out of the choir. I got out of my church choir. No I did

Because you thought professors knew better. We know gospel music moves the whole world, even government yet with a couple of weeks ago, had a gospel, uh, monazite gospel choir and his demand is going up and going away going home. And so gospel is a big thing in our community, but he told you not that you could not say it or not to stay.

Yeah. She encouraged me to get out of my church choir and stop singing gospel music because at the time they thought gospel music would destroy the Volvo cars, not destroyed, but you know, give you bad. Um, you know, a bad technique. Cause you had a certain technique that you use when you were singing classical. So you tell me you lost your soul. Well, you know, I must say it wasn’t this LSU. It was that some of the HBC use to, if you were in the music school at Southern university. Cause I know I used to go up there all the time and down, you know, in the hallways and Southern university, they did not want you to play or sing gospel music or blues and rhythm and blues. Jazz was fine and classical music, but they would take you out of the class, put you out of the practice room. If you practice gospel music of blues, it was at Southern kept you with your culture. Yeah. Many of you started in classical music. That’s basically all they wanted to study.

Now let’s fast forward. So I had to end up back at LSU,

You know, after I did my field work in new Orleans, uh, I had another year I’d needed to write then, you know, get all these interviews, all these observations, videotapes, you know, I’ve been collecting this all all year and I had to write it up now. So I went home to stay with my parents. That’s the only place I could stay for free. You know, it just right, because everywhere else I had to keep a job and do all this. I had three jobs as I was doing my field work. I was subbing as a schools. I, uh, I, uh, pay my real estate. So I was working in real estate. I’m working at Tulane university, jazz archives. So the pay, my bills, I had to make it work. So you came back. So I came back to my parents’ house to write perfectly fine with them.

They wanted me to finish too. Uh, so I, I just, and while I was writing, I started applying for jobs. I applied to different universities and I even applied to Southern university, but they didn’t need or want an ethnomusicologist at the time. So I applied to LSU, they had an opening in the geography and anthropology department. They were looking for a folklorist because they only had one person teaching the folklore classes. And, um, you know, he’s a full sort of like a folklore as anthropologist. You know, he wanted to teach some more he’s in vernacular architecture was his specialization. So he wanted to, you know, do that more. And they wanted to have folklorist to take on the folklore courses where I applied for the job, did the, uh, uh, interviewing and you always have to do a public presentation. I got the job, 86, no, 87. It was in the spring of 87 LSU for 30, 34 years or four years. So

You, you went there too, you got two degrees with it and left there and we got a PhD in India then came back and been working in LSU.

Yeah. When I got the job. Yeah. I mean, I had a time in that period of time, I went to Washington DC. Um, I received a fellowship at the national endowment for the arts. So I worked there for about six months. It was an internship sort of fellowship to learn, um, cultural development management. And so I was there and actually I was still writing on my dissertation. It was stolen. Everything was stolen when I drove in from, from to end to Washington DC, it was stolen. So that delayed that degree another year. So now my car, I mean the hard copy the disc at that time, we had the flap. It is sort of flap. It is all of our copies

That must of cost medic experience. Yeah.

It was traumatic to see all that work, you know, you know, I had to sort of recreate a lot of it.

So all that would just go, there was no other copy. Yeah.

Because I ha you know, at that time, you know, you’re just not thinking I had my copies. And what would you, my professor, my main, uh, committee chair at Indiana had a, uh, a few of the, um, chapters, but some that, you know, that had, you know, really revised, but he sent me what he had and I had to work from that. Cause I was supposed to graduate that may, you know, finish writing. Cause I had, you know, did a lot of work at home and I was going to finish writing and graduate in may. Well that prolonged.

Now did you go to be the chair of the department of anthropology?

Oh no, that was nowhere on my screen. So,

So you, you never even, okay. You been working here for 34 years and you in another 34 years, do I to be the chair one day? Well, why it never crossed your mind?

It just never crossed my mind. Um, you look at the culture of the department, uh, you look at how it’s been status quo and it was just move. And basically I was into my research and my classes and my students and doing my research. I hadn’t even thought about being chair and even had a woman chair all those years, you know? So I hadn’t even thought about being too working with my, my, my students,

You going to say yourself, and one day we’ll have a changed it or they need to do something about this, then they will cry. So when you became chair this year, how did, how did that come about? Can you share how, you know,

I was getting a little frustrated and disgusted about some of the things that were going on in the department when we were trying to make diversity hires, you know, I just made some statements in the faculty meeting and, you know, I said, you know, this just has to change. You know, we got to do better than this. And I said, um, we have an opportunity to have this diversity hire. We had four candidates in to a more black, uh, male and a female would have, they were black and two white females. You know, we were going back and forth having deliberations about whom to vote for and what they would bring to the department and you know, what this looks like and what they would do for the students and all of this. And, you know, they were going back and forth. And I thought some of some people were just being a little bit nitpicky.

So I’ve made a statement in faculty meeting that, Hey, this is, this is really needs to stop. Um, we need to move forward and do this diversity hire. And I just thought gave a brief history of me being there for 34 years. And there are some there that have been there longer than I have been. Um, but I just reminded some of them about what had gone on in that department for the last 34 years, we had had two other black professors, one passed, he died a few years after he was hired. And then another one only stayed. It was another male. He only stayed a few years and he got a bit off another university and he left. So I just basically talked about how I was treating when I first came in, how some people just didn’t even know how to talk to me.

I was a black woman, um, born and raised in the south, grew up during the civil rights era. And, uh, the other guy that left actually was, uh, from Belgium and his father was Belgium. His mother was from Sierra Leone, west Africa. And I even told him that they looked at him as the exotic other, they embraced him much more than they embraced me as a black woman from the south. And, um, but when he was, you know, he spoke four or five different languages, he had a very strong French accent. He was definitely, you know, black, you could see he was, you know, of color, but, uh, they were more comfortable with him and they were with me. Cause you knew more about the history too. I knew about history. I knew. Yeah. And I could really talk about the life I’ve had at LSU since the student, you know, you don’t need anybody to tell me, I have experientials and historical knowledge.

I know how I was at LSU in 1968 and I had to talk to him and his name was John. Right. I have to talk to him about it. Cause he, you know, he hadn’t experienced, you had to bring him up to speed. Yeah. We, you know, we talked, we had conversation, he really looked at me as kind of like his mentor because he was learning a lot about us, you know, history, the Southern history, you know, and, um, you know, discrimination and stuff. And when he was discriminated on or when he was targeted at LSU, you know, he was so appalled. He didn’t know. So I had to explain to him as this is what’s happening, you are black, you don’t look on as black, but some other people outside of this department, you know, doing this, uh, African studies is the African film festival festival.

We were doing it together, written the grant and gotten the funding to bring in the films and then have panel discussions after the films. And, uh, he was, uh, so struck when somebody wrote across the, the, we have this big poster and he had a poster on his door of his office and it said, go back to Africa, across the poster. And he was just upset. He took it to the chair, he took it to the Dean and it, you know, I w I wasn’t surprised. So I had to talk to him and, and we had good conversations about that and why that happened to him. That was an awakening for him. It really was because he had been in the U S but he had a, was in San Francisco for a while. I think he was a postdoc. He was in San Francisco for something for about a year or so before he, uh, got the job at LSU. And, uh, but he had really, hadn’t, you know, hadn’t experienced a lot of discrimination, so, or, you know, be targeted like that. And he really, he was truly, so then he really wants to, so we talked a lot about it. No.

So when I’m doing the game he got out, he sure did. But also I, you know, being at LSU afforded you opportunities to do a lot of traveling. I know you do a lot of research and study abroad in some of your favorite places. Yeah. I

I’ve been drawn to the Afro based, um, French Afro French countries like Senegal and Haiti. And I guess because, um, well, I, I know I first went to synagogue, became interested in synagogue after reading Quinland middle Hall’s book on Africanisms in colonial Louisiana. And she talked about the fact that the Senegalese were one of the first ethnic groups to come in to new Orleans or to Louisiana theory, insulate people. Yes. And this, you know, early 17 hundreds. And she talked about the fact that about 12, 13 ships came in and 11 of them came directly from Senegal. So that really intrigued me because I always thought my grandmother looked like a tall Senegalese woman. And I don’t know, I don’t know, you know, where my ancestors were, what ethnic group we came from, but I like to, you know, claims yeah.

Then you visit there quite a few times. Oh

Yeah. I’ve been there a number of times. Um, first actually joined with my husband. He was, uh, friends with some of them, the Senegalese ambassadors that came into DC and he used to shoot the photography for them. So first I went with him and then next, um, I wanted to go back and do some study in there. I didn’t, wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. I just knew I wanted to be in the Senegambia area because they were, the groups at first came here from, from, from west Africa. So I had, uh, one of the doctors that, um, Morehouse, he asked me if I would interview one of the healers that they were bringing the healer to the Morehouse medical school, because they, they had a, uh, uh, an Institute on traditional healing practices. And so they will bring this healer from Senegal.

So he asked me, he gave me the interest. He didn’t give introduction, she didn’t give interviews anymore. So he gave me a letter to give her as an introductory letter. And so from him, his doctor, Dr. Fitch and Morehead, Morehouse college. And so he wanted Nash to take the pictures and he wanted me to interview her. That’s how I started. I interviewed this. She was 106 years old when we got there. And, um, I had to get special permission to she’s a legend is very important in the country. And so I had the permission and introduction to her to go in and interview,

You say that he’ll explain

Traditional healer. Um, and that really moved me into studying rituals. I already sort of lifted rituals, but looking at rituals in Africa and the diaspora, and this was one of the ones that I looked at, what traditional healing practices. I had an uncle that ask me, well, what, what do you do when, you know, when you go to, we work with, I say, I work with these traditional healers. I had to explain to him how he is his mother and my grandmother used to, you know, some of the things that she used to do for traditional healing practices. She knew some herbs and things you can, you know, put on a soar to help it heal something that you take internally, you know, those bad stomach aches, something you do for a coal. And she, she used herbs things that she having a garden or some tree she would get off of it. And so a lot of things she did, we didn’t know what tree or what plant she was getting it from. But you know, they, in a lot of our elders, especially in the south work with these traditional healing practices, because they didn’t have the money to go to physicians. And, um, so they learned a lot of these news passed down through the generations.

In fact, when I was a boy, my grandparents stigma on my dad’s side, my grandmother, if somebody had any kind of here, but she just didn’t go to yoga, pull list, plan, or flour, because back then nobody cut grass. Like they do [inaudible] yard, whatever group they would let it grow. Natural was you tell us, go pick up pixels type of tea leaves, you know, for certain purposes and whatever him and you had. That’s just going to the doctor that wasn’t even thought you could, like you said, you call them healers doctors call it practices, physicians you’re practicing.

You’re right. They were healing. Uh, and so that’s what I was looking at. This was one of the healers in Senegal that was highly respected. I mean, people came in from Europe so that she could work with them. And of course the Senegalese, how they respected her. Now you have to realize this is a 90% Muslim country at some point in time, you know, women were not as respected or as you know, but now in contemporary times, you know, you have women that a business business women and, and, uh, and politics and all of this where a healer, you know, they, they don’t look at ritual as such in, in this traditional healing. This practice was passed down through generations, by women, in the neighbor, ethnic group, in Senegal, there around fishing villages, to Dallow those villages and there around the edges, you know, of the ocean fishing villages.

And these women are very powerful healers in that particular country, in the Muslim country. You know, you in an early age, you know, we way back, you know, when this particular healer here, she’s mum five to sec was her name she’s a hundred, six years old. Was she learned it from her mother and now she’s passing it down to a hundred, you know? So it comes through the women to lineage. You know, as I saw myself how powerful she was when, you know, some of the politicians will come and ask them if they would come to their, you know, like a political rally. Cause they have, the healers showed up depending on which one it was, that means that person is highly respected. And I mean that political person, if this healer shows up to your rally, that means you, okay. You know, you, you sanctioned by the healer.

So that’s how powerful she works. I went to one interview and they were getting ready. And so I’m, you know, I’m, I’m curious. And so what, what what’s going on. So she has an entourage of her entourage head on their regalia, all this serious colorful regalia. So you got about 10, 12 women all dressed in these beautiful colors, the same dressing. And then you got the healer there and they had to care of her. Cause she, you know, she didn’t walk very well anymore. It’s just a magnificent view to see that, you know, this is powerful weapon coming through. He is a Muslim country. You know, they respected her and most healers are respected. Even the athletes respect them that I noticed that I went to some wrestling matches while I was there, simply because it was a connection with the healer and to download this law village, I was able to go to the wrestling match. Then I was able to interview the, the, the wrestler, um, before and after. And he had his own healer there with him. He, she would, you know, put some portions and in his belt or wear around his neck. And, um, then he had this, um, this liquid that he would pour over him and that’s that’s to help him with his power. And they wouldn’t do anything without their healer, man.

Well, yeah. And that’s basically what comes from African tradition. And th th so I was in it, and then I went to the national stadium where the, the big wrestlers wrestle, it’s a whole performance, you know, you have the healer there and that you have entourage and they do their dancing and stuff. And then you got the dramas over here. It was like, [inaudible] got a great performance. Even with the basketball games, you know, it’s stuff that they have part part of the band there, and then the cheerleaders and all that. So, but instead of the healers and their entourage and, you know, their dramas, they got their master dramas with them. So you’ve got all this going on in a wrestling match. [inaudible] right. And then, you know, and you see him, the wrestlers go over and they work their healers, they do their thing. This, this is a whole ritual. And it’s amazing. It’s powerful

Is a big thing in African country. Oh yeah,

Of course we know soccer, but wrestling is the other thing that’s really, you know, they’re football and soccer, but wrestling is the other thing is serious. It’s very serious to have your own healer. She got to be, she got to have your healer there. Yes. The national stadium, I went to wrestling matches there in, in one, in a small village. And then I had the, you know, I was falling in the wrestling. I wanted to see what the hell is happening. That interaction between the wrestler and the healer, that dialogue that they were having between them. It was powerful. I don’t know what all of a sudden, the little day that they were in the liquid, that they pour over them. So they didn’t just do, like, they don’t work.

He has to lose, but, you know, it’s, it depends on who has the most powerful healer how’d you end up in Haiti. Haiti was another country that I had an interest in for a long time, again, because of the, the, um, the influence of Haitian culture on Louisiana culture. And I’ve always wanted to go to Haywood. I, I did a project with the metals museum in north Louisiana, um, with Dr. Bria who was a Haitian, uh, collector. He was a physician, but he was a collective Haitian art. And, um, when they asked me to work with that museum and they wanted me to do a presentation on Haitian culture, I said, well, it’s good to do a historical presentation, but we need to know what Haitians are doing that in Louisiana today, because they, they doubled the population of Louisiana after the Haitian revolution. So I said, so we still have so much Haitian influence here and the culture and the language in the food.

So let’s find out what’s going on today. And so I, you know, so they did that. They, they gave me money to go out and interview the Haitians that were in new Orleans and in Shreveport because the exhibit was in Shreveport. So that’s how I started getting into the Haitian community by going into, um, into new Orleans and doing interviews there. And I interviewed all the Haitians that when Shreveport at the time, which was 12, Dr. Bria was one. And he took me around to all these Haitians, to their homes. So I can end up getting him. Cause I was looking really at what were the things that they had maintained of their culture after coming to Louisiana. I mean, these, you know, contemporary Haitians, so to speak. So I wanted to know what major, um, things that they were still doing to maintain their Haitian culture. You know, I knew that was important to them. So, um, and so it was a very, um, enlightening ex exercise that I did. And, you know, I learned a lot about Haitian culture through talking to the people.

Are you saying that then the new Orleans doubled in population? When

Was this after the Haitian revolution, after the Tucson overture, the Haitian revolution over in 18 0 3, 18 0 4. Of course there were mass migrations before the revolution was over because the planters were leaving, going to Louisiana, Cuba, wherever else they could go. But of course they were taking the insulated people with them.

So they came. So the Haitian, the new Orleans population grew overnight because of the migration migration of Haitians coming to new Orleans in 18 hundreds. But they came, we came, came back to the way of, uh, the slave masters broadly.

Yeah. The slave masters brought, yeah, they’re, they’re enslaved people, but there were also free people of color that came. So it wasn’t just enslaved people, but the free people of color also came and that brought new Orleans into a three tiered society that the white, the Creoles and the enslaved, the Creoles and free people of color with all free people of color are not considered Creoles. And, but so they had, but they basically had the three tiers to society.

Since I got an anthropologist in, that’s always been the big question. Well, what is a Creole?

You know, it depends on the time of history that you’re talking about. Some in one time they considered Creoles to be people of another descent. I was born in Louisiana. So like, if you’re European and your parents came to Louisiana and you were born in Louisiana, then you were creed up. And then other people say, well, you know, another definition of course is when you have the mixture of, uh, black and French or black and indigenous people, they’re considered like Creoles too, you know, a black and you know, some Spanish, French, whatever,

Ed, the Jordan Smith, uh, one of the renowned geologists around the Louisiana area said that also Creole was a term like, like you just defined. She said for when the Africans came to this country, but when the child was born here, it was considered a career. Yeah. And as my own, my first time here, you know, we grew up pretty. I had to do with the complexion of your skin. You would like a flexor. He was considered a Creole. But I knew when I grew up that wasn’t true because there was people, Creole that we called cochlear, and it was a different, you know, a dark to light. But I put for the most part that need like light skin for the, for these days at time, they use it more for the lighter complexity.

Yeah. For mix, because you have, you know, mixed blood, which, which are not light, some are dark and they’re still considered Creoles. So it depends on, you know, who you mix with.

What kind of work were you doing in Haiti?

Well, um, I was actually, uh, first started going in, looking at carnival because I also do carnival in new Orleans, Mardi Gras, Indians. Okay. So you’re going to get that your favorite subject. But I went there because I was always interested in, um, the indigenous population and how they are represented in carnival. And there are Haitians who also honor their indigenous populations to Arawak Indians, you know? Um, and so they dress like they’re awake in the ENS in, in carnival. And it’s a lot of bands events. So-so

Haitians in Haiti have a Mardi

Gras. Kitchen. Yeah, yeah. What they call it carnival. And they have to, as a matter of fact, they have one and of course the main they call it the national carnival and port us for Spain. Uh, I mean, Port-au-Prince Trinidad. I do Trinidad too, but the other one is Jack male. They have a traditional carnival and Jack mail. It happens the week before the national karma. So I went to the national carnival first and this was right after the earthquake. So they were moving it around. They didn’t have an input. They, they moved it around to a cap patient, which is in the Northern part of Haiti because they wanted to take it to different cities. So they could bring revenue to those cities because, you know, if you have carnival people coming from, you know, full all of the countries, they comment to Haiti. It’s like they come and Trinidad the new Orleans, you know, with the Caribbean folk.

Yeah. So are you telling me that even in Brazil, so mighta Gras, carnival is a part of the culture of who would be

Many countries have carnival, um, yeah. Brazil, uh, Haiti, Trinidad, uh, a number of other countries, you know, some of the other, some of the other, they may call it something different. Like in Jamaica they had Junkanoo.

Okay. But I’m saying that, you know, for the most part we Louisiana with European, I mean, you got was a European type of thing. Well,

It was basically started in Europe. Yeah. And we know when we had the diaspora began with, uh, all of the, uh, uh, people of African descent, they had carnival wherever they were, you know, so this is now it’s in these countries is a mixture of the culture of that country as well as European culture. So you have these cultures mixing up for a carnival monocrop. Now in some areas like new Orleans, they have, you know, the big float parades, which is basically kind of like the European side of it. But in the black communities, they walk the streets and it’s sorts of different type of carnival. As a matter of fact, they didn’t even call it Mardi Gras, they call it kind of up, you know? So you have those influences from Haiti because the Haitians came into new Orleans. And so you have these mixtures. I look at like you take the modern grain is for instance, a walking, uh, carnival walking in the streets, parading through the streets during precessions. And there are a combination of west African influence, Caribbean influence and indigenous influence. So, and because it’s on my grind day, a lot of people say in European influence because it’s during that time. But you know, it’s those a combination of cultures that are coming together,

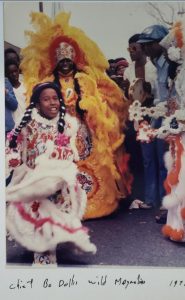

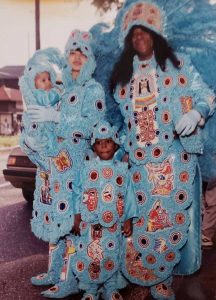

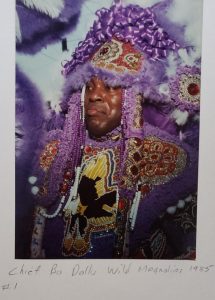

But the Indians just don’t come out on Mardi Gras day. They got something they call super Saturday. Yeah. They

Will. Even before super Sunday, they do St. Joseph’s day. And I can’t, you know, I’m still, I still ask why St. Joseph’s day. Well, you know, there’s a lot of Catholics in new Orleans. It was the highest Catholic population of blacks. So another day to day come on, they wanted it. That was a traditional one carnival and St. Joseph’s state is just another day to celebrate another day. We can wear our, since the super Sunday started because of the protests, uh, with, um, Jerome Smith and tambourine and fan club, basically the youth of the community and tree me. And he started super Sunday. But looking at it as a way to protest destruction of many of the black homes in the treatment area, when they brought, when they destroyed Cleveland avenue, they still destroyed all the trees. It was kind of like a Parkway. And it was, it was, um, lined with Oak trees and grass where the community would congregate for different things, all sorts of community activities. Well, when they destroyed that and pulled in the interstate, they destroyed a lot of them

Ran the interstate drinks straight through as user would stay straight through the

Community, right through the community, the store at the park area and the home many homes and black businesses,

Cleveland avenue, Clayborne avenue, it goes down to cross as the city. Yeah. So now tell them what was super Sunday, what happened?

Well, what happened? He was, it was a sort of a protest March marching, you know, because of the urban, urban renewal.

So, so, but not end up being a party.

Yeah. Yeah. Well, it started as a problem in the story that I get from several people that 2d chief, big chief Tootie, Montana, you know, new Jerome and they used to talk and he knew that Jerome was having this protest March, you know, to speak about what had been done to the community. And so he decided that he was gonna March to, he ain’t gone Jonah, but he joined them in his Indian suit. So of course, when people see big chiefs 2d out there in his Indian suit, they start dancing. Some of were put on that very big T 2d. I hear serious. So they say, okay, we go join them too. And that started the first, super Sunday in the downtown area around tree. May you have Orleans avenue dreamy? That’s that, that’s that area by the municipal auditorium congos and that bar from Congo square and all of that, that’s, that’s the tree main area.

And that’s where the first hoop was done suddenly started. And then the uptown, the doubt that was downtown for the uptown folks to say, well, we going to have a suicide. So then the uptown decided that they would have a super Sunday. And then the wet years later, the west bank decided that they were going to have a suicide, this and this. And now you have three super Sundays on three different Sundays. And every day that Indians can come back out again with their suits on and the, the skeleton man, the baby dolls, all of this is like, you know, the black monograph, this black carnival, they celebrate with a celebrated three more. They make the three more days.

And you, I understand you working on a documentary.

Yeah. Well, there have been a number of documentaries, um, that have been, uh, filmed on the Indians, but I just thought that I would do one really concentrating on the music because the music is a very important to the ritual. So yeah, it’s a street ritual and it’s, it’s, it’s very important, um, with the procession, because basically there’s new, pre-sessions on carnival and it’s not a parade. It’s a procession where the different groups, different Indian gangs meet each other, and it’s a mock battle they’re warriors and they have this mock battle on the street. So after, um, you know, um, the, the, the super Sundays, it’s this kind of a parade, you know, they just parade in the streets so everybody can still see their suits again and see how beautiful they are.

Yeah. Really beautiful. We had two home today. Thank you for inviting us here. And you’ve got some wonderful pictures of some minor grinding. He was right behind you.

We’re working with him a long time

And that’s what junior, your husband and there’s, you know, really put us, spend a lot of time.

Yes. And it’s a complex ritual. Most people think it’s just something they do on carnival day or super Sunday. St. Joseph’s but many of the participants actually live. Would you be leaving? Year-round it’s a life cycle, right? I mean, it’s a part of their lives. No, of course. No question would be,

Uh, any like the need, the native American, or he just called himself UDL.

Both. Some of them actually have native American ancestry and some don’t, but those that don’t act like it. And it’s sacred. It’s a sacred thing. Whether, you know, you really know you have some indigenous ancestry or not. It’s been, you know, you know, because they are celebrating the indigenous people.

That was a little boy. And I always tell a story that, because my grandmother, on my dad’s side, she would always say that, you know, she was native American and she would always, she never give us a story or the history about who we are. And I guess when all day we would look at, when we looked at her, we think about what they call, what they call a squat, either a fibia, uh, indigenous person, when you call them, when, you know, that’s kind of what she looked like to us, from the image that we had on what, in watch a TV when she was always tell then yeah, [inaudible] was, it was embarrassing. You don’t need to know this is not important, but she spoke French and wouldn’t have system would come to town and speak in French, French, French, but they would never let, let us learn everything about her culture. It was like, it was, you want me to know this not even important, like, you know, is behind you, you moving all you in America. Now, that’s kind of how I, when I think about that as I’ve gotten older, yeah.

Well, a lot of Indians, well, indigenous people were enslaved to at one time, you know, when, when, when the, um, they brought the enslaved people from Africa, they also enslaved indigenous people. And that’s why they had a really certain Alliance with Africans and Indians and early in the early, um, colonial period of Louisiana. And so this has, um, you know, it’s gone on three years, so they enter intermarriage and everything. Um, you had certain things like, well, the traditional healing practices, for instance, that one with being with the environment, um, religious practices, you know, so th there were a number of things that were, uh, similar with the two cultures. And I’m sure you heard of the story, how the indigenous people would Harbor the runaway slaves. They knew the land. They knew that it was a swamp land in new Orleans, and they knew the land. They knew how to survive the land and, and the Africans, you know, they could adjust and they adapt it, you know? So they, they harbored a lot of them, runaway slaves.

I hear a lot about that story going to a slide there. A lot of it was hiding out.

The other thing is the indigenous people are the, they, they help to keep the colony a lot, the French colony alive in Louisiana,

Or about them, how to grow food,

How to survive the land. And, um, they would come in and sell their produce in the fresh mark. They would also come in and sell their produce and Congo square. Many people think it was the Africans that started Congo square. No, it was indigenous people at that time. Congo square was right behind new Orleans. New Orleans was the French quarters. Well, we know as the French quarters today, that was it. That was new, new Orleans and Rampart street was the back of new Orleans. And then that started tree may was right out the ramp, foster Palestine, you have Congo square. So they would come to the outskirts of the city to sell their, produce those outskirts metal with his heart, for them to believe these days. But that was the outskirts to see the French quarters. And they would not only would they sell their produce, but you know, you have the mixture of the languages.

Now you have the dances, you have the rhythms, you have the drumming, you know, when you got the indigenous end and the Indians, I mean, the, the indigenous people and the Africans doing all of these things. So all this is coming together in one. And that’s, that’s that we look at that as the core of the city, because not only the cultures were coming together, but economy was coming together. They would, they were selling things. You know, this is a good thing about jazz and all that came out of Congo square. It was like the core of the city. It was, it was the behind the city,

French quarters, which I’m still this age, but it’s called the French quarter, but it had Spanish pocket tech.

Yeah. Well burn a large part of the French quarter burner. I forget the exact year, but then despair. But then the Spanish were the colonial powers. So they of course building with Spanish influence, but you still have a lot of the French influence around, but yeah, a lot of it is Spanish influence because it was colonized by the French first, then the Spanish, then the British came in. So during that time, the quarters burned, it was the Spanish that brought it back in Spanish.

Okay. So that’s, that was bourbon street was, that’s why it’s still a main street. So that lasts a long time. I wouldn’t get excited, started talking about,

We love you India. So let’s get back to tell me about the documentary I’m doing that now, because I thought there was a need to sort of feature the music because the music is, um, so important because I look at the music, the Indian music, the rhythms, the drumming, uh, I look at that as being a strong influence on the early RNB of new Orleans. Now that’s a large part of the documentary, but I also look at the systemic resistance of the Indians because they always resist as assistants. They say, we’re not parading, so we don’t need any permits. You’re not doing that. We don’t need permits. And so, you know, they just, they, we, no, no, we don’t need any floats. We can walk through the streets. [inaudible] Yeah, he’s still doing it. That’s right. And the other thing I remember both Alice, which was an ended in big chief told me once, you know, he passed his past now, but he told me once he said, well, you know, they wouldn’t let us come on canal street in St. Charles or Cedar parades. So we just decided with all make operates, we do our thing separate from them. We, you know what I’m saying? That’s what exactly what they did. You know, there’s

The dark side was already where they were yet. So they weren’t included,

It’s turned around, turned around the homeless. But yeah, but again, resistance, it was this discriminatory practices. They would let the blacks go in there. They couldn’t, they couldn’t go on this street. You can be the first ones to see the parade, you know, at this stage, you know, with carnival, even with monograph, you know, it was discriminatory practices. So again, that’s how they just resisted and did their, okay. Now, are we talking

About discriminatory practices? I did a little research enough on that. How long have you been in it at LSU?

Well, it’s a professor 30 to

40 days. You’ve been the lowest paid [inaudible]

For 34 years. That’s the true, the research, you know, it comes up,

Is that true? That’s that’s discriminatory or practice or that just, you just didn’t qualify to be up there with the rest of

Them. It wasn’t equitable. It was not equitable. What’d you mean by equitable? I was not getting equal pay. And most women at LSU don’t get equal pay as the men, not at LSU, they don’t do such a thing. He said, you tell him, Alex,

You do not pay the women to save her day to be in it. What’s your degree maybe. Cause you went to university and had this qualifying LSU. You, you, you are worth the lowest fee. Even to this

Day. I was the lowest paid full professor in my department that, that I do know

Recently, well recently, I mean, 10 years ago,

A few months ago, a few months

Ago you were still, so [inaudible],

I’m just saying right now, uh, prior to I was the lowest paid professor, Louis paid full professor in my department, even after, you know, one, it come behind me.

He was someone came years after you were still making more than Mia male. So that’s a common practice.

Well, uh, women do tend to be paid less during the same jobs, you know, definitely on university campuses, but in a corporate world too. So now you fight for reparation to know, or what would they call that restitution. So, so how

Can, how can that be corrected? So that’s Cherokee. Can you have any impact on making a

Difference? Well, I’m certainly going to try,

Like I see all of that and takes me with the word trying, are you going to do something well? Yes. Yeah. Yeah. W what are some things you’d like to do to bring some justice equality?

Well, uh, I would certainly like to, uh, increase the reach and our department. And when I say increase the reach, I mean, as far as, as far as recruitment and, you know, engagement retainment of students and faculty members, um, because again, we don’t have a good record in diversity. My department does not.

LSU has his first president. He came on right after you did, uh, doctor take two intake and William the first in the sec to be the president and then the CEO of the university of African descent. So LSU has made a history as a major leap. So what’d you think about, have you had a chance to speak

With him chance to talk with him yet? And we had a forum last week, but you know, it was a forum for all faculty, you know, who wanted to get on the forum, but it was basically to talk about the COVID pandemic. Um, but in our department, I, you know, I would, I would just like to see some more of a diversity equity and inclusion. And, um, and I, I look at diversity is, um, not just being, not just looking at it demographically, but I look at it as being, uh, you know, having a diverse culture. So, I mean, you, you, you, you have an ingrained within the system within the department and not just to have the numbers there, but really aren’t engaging with him. I’m not supporting them and doing all the things, you know, that you need to do to retain people. So it needs to be a culture of the department, not just having the demographics, you know, and so I will work hard, uh, doing that. I mean, I’ve done that at the university, in my old tenure being there, you know, where I could. Um, and so I intend to do more of that. I would like to see us, you know, being a more diverse department and including, uh, others, um, and making them feel,

Would you like your legacy to be when you leave the department as the chair, though, what’s what you’d like to implement. Some new things

Really liked to be a catalyst for institutional, um, change. Um, and in that way continue, um, really make an impact with diversity inclusion and equity, uh, this mansion, um, and do that embarrass ways. And I mean, with faculty, as well as graduate it as well as students, you know, undergraduate as well as graduates increase our numbers, you know, our numbers are low and it was low before COVID. So we can’t, we can’t blame COVID for low numbers

And students, students,

Um, enrolling in graduate

For as a diversity students

As a whole. Yeah. We, you know, our numbers are kind of low right now, so I like to build those up as well as

The diversity part. So it was hard to get students to enroll in anthropology.

Do you have to let them know about it? And it’s not hard to get them enrolled? I mean, I think I anthropology numbers up more than others, but, um, but on both sides, geography and anthropology, I would like to increase the interval.

Do y’all do many outreach program

In your department. One of the things that I want to do more of, we have done some, but I would like to do more outreach in the community and going into the high schools and talking about these disciplines, because I mean, we got geography and maybe, I don’t know, feel for sixth grade or something that we never got anthropology, you know, so I have done that already, but I would like to see more of the faculty members do an outreach program to the community because if students need to know, you know, most of them don’t know about the disciplines before they come to college. And a lot of them will take it as say for instance, in elective or their social science requirement, and then maybe they’ll get interested in it and, you know, say, I think I want to go on and have a, um, you know, get my degree in my bachelor’s department

For 93 years. So that means a pretty old department. We have not had a major impact on the

Major impact. I’m just saying now I would like to increase the impact. You know, I mean, we have a lot of, uh, graduates that have gone on and done wonderful things in various parts of the world, you know, but I would like to see it happened

More. One day I was talking with you. You told me a very interesting story that I, uh, need to be repeated because this is the soul is funny. And the showing you how diverse you are too, and how much you love your people. You love your community and you want to do anything to, uh, support live your community. But you talk about telling this story about, uh, you love you music, although you could say gospel music, you know, when you went to uni attended LSU, but you had a friend who had a record store and he had passed and you had to be out of town. You wanted to collect the music, but it just was doing it to one of the way you remember last

Night. Yeah, it was, um, it was, uh, w w w it was a music store, but they also supplied a lot of the regalia for churches and choir’s Bibles, uh, uh, heroin’s music store. And, um, it was, you know, I would go there and talk to the person that owned it. And he was, you know, he was getting older and he wanted to retire and you wanted to close up the store and I encouraged them and said, well, before you close it, let me talk to LSU about buying the collection, because we have a, a music library within the large, uh, university library. So I said, well, let me talk to LSU and see if I can get them to purchase the music. I said, they probably don’t want the Bibles and the Sunday school, class materials and all of that. They had communion things you use for communion the whole bit.

He used to supply that to the national Baptist convention, which most people don’t know that they cause most of the folks in Chicago, but no, we had this little store here in Baton Rouge that supplied a lot of the, um, materials, um, for, for, um, for churches. And so I went to Ghana, uh, another one, the abroad programs that I, uh, led and he died while I went to God. And one of my friends knew that I had been, you know, connecting with him and, you know, wanting to, um, get LSU to buy his collection. And she, she contacted me and well, I got back maybe two days after the funeral. And I was able to get the number of his relatives, call them to find out well, where is all the info? All the materials that were in the store, they say, oh, we got a dump truck and had them to take it to the dump.

I thought you did what I said. Okay. Which doctor did they take it to? They gave me the name of the truck, the number of the dump truck. And they told me wasn’t done. They took the music too. I got, my dad, got the pickup truck and I got my dad to go with me. I had my boots on, I have some gloves. And I went to the dock to dig out the music, you know? And that was so important because not only was the guy that honest though did not. The second, this is the second guy that owned it, that I was able to talk to the first one who was the actual composer and the owner of the store had already passed, but he composed a lot of gospel music. Then he actually printed gospel music for other composers and arrangers of gospel music. So he had all of this and he’s shopping at a printing machine. He actually printed the music in his shop and he threw it away. They just, you know, this is some of their relatives. They’ve just wanted to bury him, get rid of all this stuff and go back to Chicago, wherever they came from, they actually had all that taken to the dump. So I went to the dump and I asked the man, I said, okay, I got a pickup truck. I got him. Right. He’s saying, I can’t let you in the dump.

That’s dangerous. I said, why I got on my boots? I’m sorry, I can’t. He said, another truck has done on top of that truck. That game he’s I can’t let you in that. And then with that, I was, I was literally, I mean, I was actually sick. I mean, my stomach was upset. My sister was upset. I was, I was just upset. Then I wanted to, I was going to dig for that music that they get about. I was thinking about getting that music sheet, music, gospel music that composers black composers said, I don’t know where else that I could have found that all that together, right there in that shot. I was so, you know, I had gotten some and I got one of the guys, another black guy that was in the music school at, you know, told him about, he got part of the printing press.

He actually got some of the, I don’t know what you call them, but they, they had, they slaves that you print on. He got some of that. He got some music, he’s a musician and music school. And so I got him to go in and get some, we were buying the music from him and he was selling a tours for the prices that you paid for 30 years ago. And then I would give him some more. I said, but I could get LSU possibly to buy this from you. So we could put it in the music library and archive. You know, I got students who could catalog it and we could archive this music and put it in LSU, roll away. Except what I had already bought from him. At another time I had called each time I go, I buy something. I bought big print Bible. I buy something every time I go. And that’s how I got some of the music, but he had tons of music that people probably didn’t even know was there anymore. I wasn’t interested. Just people just didn’t know it was dead. And it went to the dome. I was just, I was just, oh, I was upset to upset that man with not, let me get them. [inaudible]

yeah, I can’t let you take my job. Let this crazy for music. You take your, be the series. Yeah. That’s you know, that was a treasurer. You know, it was a treasure that we can never get back. These are black composers on gospel music. Yeah. Do you know how much people would pay to get that today? Or just to study it? Just to go into the library and use it and study it. It was cold in the dump. I was really upset. I made it, took me a while to get over that. I really,

Where we could feel the, a, you just pointed to dramatic experience of your traumatic experience. What about the experience that I heard one time was in college or coming out of Canada. Do you want to travel through Africa? Really going back to the travel, but you want to do the whole nother?

Yeah. Well, you know, I knew I wanted to travel through, through Africa, west Africa, but I wanted to see some of the other areas too. And I don’t know. I always had this dream, a vision about me traveling through Africa with my backpack and my baby. Yeah. I think at some point I was going to have a baby, my life. I wouldn’t have a baby, but they was going with me wherever I went. And so I saw my baby in my backpack or in my, you know, you know, how to African women had their babies wrapped around and wrap them and they put him on his stomach. And then I had my backpack on, I saw myself traveling through Africa like this, didn’t get the baby. I got this bag.